The mental health of a nation is a cornerstone of its overall well-being, yet it remains a public health priority that is consistently under-prioritized, under-funded, and under-evaluated.1 In an era grappling with unprecedented global challenges, including the lingering effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, the World Health Organization (WHO) has released the seventh edition of its landmark Mental Health Atlas 2024. This comprehensive report serves as a vital tool for tracking global progress, identifying critical gaps, and guiding decisive action toward the ambitious goals of the WHO’s Comprehensive mental health action plan 2013-2030.1

For India, a nation whose unique demographic and socioeconomic profile positions it at the intersection of a mental health crisis and immense potential, the Atlas is more than just a global overview. While the report does not dedicate a specific chapter to India, its findings for the South-East Asia Region (SEAR) and Lower-Middle-Income Countries (LMIC) serve as a powerful and highly relevant proxy for understanding the nation’s mental health landscape.1 The Atlas also recognizes the vital collaboration of key mental health focal points and contributors from India, including Saurubh Jain, Neha Garg, Shalini Kelkar, Pratima Murthy, and Atul Kotwal.1 Their contributions underscore that this is not just an external assessment but a report shaped by local experts. The central question the Atlas helps to answer is both urgent and profound: What do the latest numbers reveal about India’s progress, and where do the most significant challenges lie in transforming mental health from a neglected issue into a national priority?.2

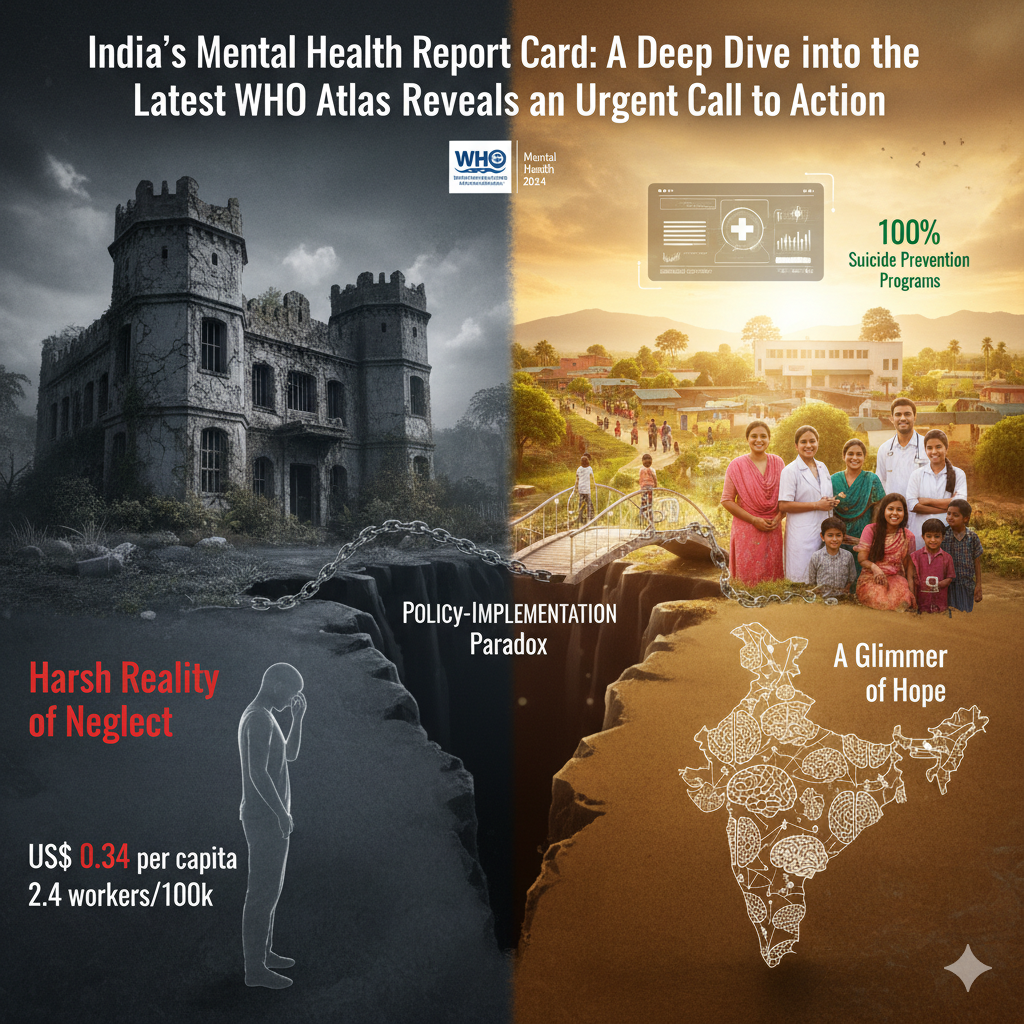

The Harsh Reality of Neglect: Funding & Workforce Shortages

The most glaring and immediate finding of the Mental Health Atlas 2024 is the stark and persistent inequity in resources for mental health care. The report paints a picture of a world divided into two distinct tiers: one with robust, well-funded systems, and another struggling with minimal resources. This “two-tiered” system of care is most visible in the data on government mental health expenditure and the size and composition of the specialized mental health workforce.1

A Stark Financial Disparity

On a global scale, the median government expenditure on mental health stands at a paltry US$ 2.69 per capita.1 For Lower-Middle-Income Countries, however, this number plummets to a staggering US$ 0.34 per capita.1 This represents a difference of almost 194-fold between high-income countries (HIC), where the median is US$ 65.89, and LMICs.1 The disparity extends to the proportion of total government health expenditure allocated to mental health. While HICs dedicate a median of 4.3% of their health budget to mental health, LMICs allocate just 1.0%.1 This is not merely a funding gap; it is a profound structural deficit that demonstrates how the promise of universal health coverage is failing for mental health in low-resource settings. Without a baseline of financial commitment, countries like India, which carry an immense burden of mental health conditions, cannot even begin to build the systems necessary to meet the needs of their populations.

A Critical Workforce Crisis

The financial data directly correlates with an equally severe crisis in human resources. The global median number of specialized mental health workers is 13.5 per 100,000 population.1 For LMICs, this number is a critically low 2.4 per 100,000 population, a 28-fold difference compared to HICs, which have 67.2 workers per 100,000.1 The deficit is particularly acute for the most advanced specialists. While HICs have a median of 7.0 psychiatrists per 100,000 people, LMICs are left with just 0.3 per 100,000.1 For mental health nurses, the largest component of the specialized workforce, the median in LMICs is just 0.7 per 100,000, compared to 27.0 in HICs.1

This data reveals that the limited workforce in LMICs is heavily dependent on generalist and allied health professionals, without the capacity for complex diagnostic or psychotherapeutic interventions from advanced specialists. The crisis becomes even more dire when examining the data for children and adolescents. The global median for specialized mental health workers for this demographic is a shocking 1.5 per 100,000 total population.1 In LMICs, this figure drops to a median of just 0.12 workers per 100,000 total population, which translates to almost one worker for every one million children.1 This immense deficit means an entire generation’s mental health needs are going unmet, with long-term consequences for national productivity and well-being.

The sheer scale of this resource gap means that access to care is not a matter of need but a function of national income. For India, as a major LMIC, this data signifies that while it has the largest number of people living with mental health conditions, it also has the fewest resources to treat them. This creates a severe treatment gap and places an immense burden on families and communities, as evidenced by the high out-of-pocket costs and reliance on social support systems. The following table starkly illustrates this global inequity.

| LMIC (proxy for India) | HIC (High-Income Countries) | |

| Government Mental Health Expenditure per Capita | US$ 0.34 1 | US$ 65.89 1 |

| % of Total Government Health Expenditure | 1.0% 1 | 4.3% 1 |

| Specialized Mental Health Workers/100k Population | 2.4 1 | 67.2 1 |

| Psychiatrists/100k Population | 0.3 1 | 7.0 1 |

| Mental Health Nurses/100k Population | 0.7 1 | 27.0 1 |

| Child & Adolescent Workers/100k Total Population | 0.12 1 | 4.56 1 |

The Two Steps Forward, One Step Back: Governance & Service Delivery

The Mental Health Atlas reveals a complex picture of progress in policy and a simultaneous regression in implementation. A high percentage of countries have made significant strides in adopting mental health policies and laws, yet the data shows a deep, systemic “policy-implementation gap” that prevents these noble intentions from translating into real-world change.1

The Policy-Implementation Paradox

The report notes encouraging trends in mental health governance. A significant 81% of responding countries globally, and an impressive 100% of LMIC respondents, reported having a distinct mental health policy or plan.1 The report also highlights a growing alignment with human rights, with 73% of countries reporting their policies are compliant with international instruments.1 The trend is also positive for legislation, with 72% of countries having a distinct mental health law, and 56% of SEAR countries reporting such laws.1 An increasing level of collaboration with non-governmental organizations (NGOs) was also observed, with 79% of countries reporting functional collaboration.1

However, the reality on the ground is far less optimistic. Only half (50%) of all responding countries reported that their policies were both implemented and fully compliant with human rights instruments, and for LMICs, this number drops to just 46%.1 The primary reason for this contradiction is a lack of financial follow-through. While HICs report allocating financial resources to their mental health policies 87% of the time, LMICs do so only 22% of the time.1 This stark disparity suggests that the adoption of a policy is often a performative act, a symbolic gesture to align with international agreements without the political commitment to provide the necessary budget and resources for implementation.

The following chart visually demonstrates this paradox, highlighting the difference between policy on paper and its real-world impact.

| LMIC (%) | HIC (%) | |

| Countries with a Policy/Plan | 100 1 | 87 1 |

| Policies Compliant with Human Rights | 73 1 | 77 1 |

| Policies Both Implemented AND Compliant | 46 1 | 66 1 |

The data for the chart is drawn from the Mental Health Atlas 2024, representing the percentage of responding countries in each income category.

The Slow March of System Reform

This lack of funding and political will manifests most acutely in the slow pace of mental health service reform. The WHO has long advocated for a shift from institutional, hospital-based care to community-based models. Yet, the Atlas shows this transition is progressing at a glacial pace. Globally, only 9% of countries have fully completed the transition.1 A majority (53%) remain in the early stages, with more beds and services still concentrated in psychiatric hospitals.1

This persistence of institutional care, particularly in LMICs, is not just a matter of inefficiency; it is an ethical and human rights crisis. The report reveals a troubling pattern: the global median of inpatient beds is 10 per 100,000 population, with a staggering 62% of these beds located in specialized psychiatric hospitals.1 Outpatient facilities in LMICs, the very cornerstone of community care, are dangerously scarce, with fewer than 0.1 facilities per 100,000 population.1

This systemic failure to build discharge pathways and community support forces individuals into inpatient care. The result is a cycle of prolonged hospitalization and coercive practices. The report found that a concerning 49% of all psychiatric hospital admissions globally are involuntary.1 Furthermore, LMIC data shows that more than 10% of inpatients have a length of stay of one year or more, and more than 15% stay for over five years, which is a significant indicator of a system that fails to promote recovery and reintegration.1 For India, this data means that even with a strong national mental health policy, the lack of funding and trained staff means the policy remains largely aspirational, and the vision of community-based care remains a distant dream.

A Glimmer of Hope: Prevention, Promotion, and Digital Preparedness

Amidst the sobering data on funding and service gaps, the Mental Health Atlas 2024 reveals pockets of unexpected progress, offering a glimpse of what is possible when there is targeted political will. These glimmers of hope are most visible in the areas of prevention, digital services, and emergency preparedness, where the SEAR region (which includes India) stands out as a beacon of positive change.

A Beacon of Hope in Suicide Prevention

The most impressive outlier in the report is the performance of the SEAR region in suicide prevention. The data indicates that 100% of responding countries in the SEAR region reported having a suicide prevention program.1 This is a significant finding that stands in stark contrast to the global median and other low-resource regions.1 While the report notes that the sample size for this region is small, which makes the number statistically unstable, it is not a reason to dismiss the finding. Instead, it demonstrates that concerted, targeted efforts in prevention can yield results even in resource-limited settings. The data also reveals that 80% of these programs are considered “functional,” meeting the criteria of having dedicated resources and a defined plan for implementation.1

This positive momentum extends to mental health promotion. The most commonly reported functional programs globally were for early childhood development (86%), suicide prevention (80%), and school-based mental health (78%).1 The SEAR region’s strong performance in these areas highlights a potential area of strength for India and a model to build upon for the entire region.

The following chart illustrates the outlier performance of the SEAR region in suicide prevention, a rare positive data point for low-resource countries.

| SEAR (%) | LMIC (%) | HIC (%) | |

| With a Suicide Prevention Program | 100 1 | 37 1 | 67 1 |

The data for the chart is drawn from the Mental Health Atlas 2024, representing the percentage of responding countries in each income category.

The Rise of Telehealth and Emergency Response

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed the fragility of traditional mental health services and created an acute, undeniable need for remote and crisis-oriented support.1 The Atlas reveals a direct and rapid response to this crisis. The adoption of tele-mental health services has surged, with 63% of responding countries globally reporting their availability.1 The SEAR region is a high adopter, with 78% of respondents using these digital services.1 Similarly, the number of countries with a mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) system for emergency preparedness has increased dramatically to 65% from 45% in 2020.1 The SEAR region again demonstrates strong leadership, with 89% of respondents reporting such systems.1

These findings show that when faced with an immediate, high-stakes threat, governments can and will innovate and allocate resources. For India, this demonstrates a critical capacity for rapid adaptation and a potential roadmap for how to sustain the momentum and integrate these new, responsive systems into the permanent, everyday mental health infrastructure. However, the report also warns of a persistent “digital divide,” with only 21% of low-income countries reporting the availability of telehealth services.1 This suggests that equitable access to these new technologies remains a significant challenge.

The Unseen Picture: The Struggle for Data & The Unmet Need

One of the most insidious findings of the Mental Health Atlas 2024 is the widespread inability to collect and report on crucial data. This struggle with information systems is not merely a technical problem; it is a symptom of a deeper issue—a lack of accountability and a systemic neglect that makes the problem of underfunding even harder to solve.

The Invisibility of the Crisis

The report notes a worrying trend in data submission, with a lower overall participation rate of 74% compared to previous years.1 This decline indicates an ongoing challenge with national data collection and underscores the urgency of improving information systems.1 While 58% of countries report having a nationwide digital health record system that includes mental health data, significant gaps persist in collecting key indicators like treatment outcomes and physical morbidity.1

The difficulty in tracking progress is most evident in the data on service coverage. The Atlas’s findings on service coverage for psychosis, for example, are based on a small and statistically limited sample of just 22 countries, highlighting the widespread inability to accurately measure how many people are actually receiving care.1 Without reliable, routine data, it is impossible to make an evidence-based case for increased funding. This creates a vicious cycle where political and financial commitments continue to lag because the true extent of the mental health crisis remains “invisible” in official statistics.

The following table highlights key data gaps in LMICs compared to HICs, revealing what countries in this category are missing.

| Key Data Gaps | LMIC (%) | HIC (%) |

| Digital Health Record System | 54 1 | 74 1 |

| Collecting Data on Involuntary Admissions | 45 1 | 66 1 |

| Collecting Data on Treatment Outcomes | 46 1 | 72 1 |

| Collecting Data on Physical Morbidity | 56 1 | 79 1 |

The data for the table is drawn from the Mental Health Atlas 2024, representing the percentage of responding countries in each income category.

The Unmet Needs of the Most Vulnerable

The data gaps become more concerning when examining specific populations. The report reiterates the dramatic lack of a dedicated workforce and facilities for children and adolescents.1 This demographic’s needs are largely going unmet, a profound systemic failure that will have long-term repercussions for the nation’s future. Furthermore, a lack of accountability is evident in the low number of countries (49% globally) that maintain a registry for the use of seclusion or restraint.1 This indicates a critical lack of oversight and a failure to protect the human rights of service users in the most vulnerable circumstances.1

A Path Forward for India: From Report to Reality

The WHO Mental Health Atlas 2024 is more than a diagnostic tool; it is a comprehensive report card that reveals the areas of failure but also the seeds of success. For India, the findings provide a clear roadmap for action, highlighting what needs to be done to move from chronic neglect to proactive care.

The first and most critical step is for policymakers to translate national mental health policies into costed, time-bound plans with dedicated budgets. Without this foundational financial commitment, the vision of a transformed mental health system will remain an unfulfilled promise. Second, there must be a concerted effort to invest in information systems. This involves strengthening the national health information systems to routinely collect and report on key indicators, especially service coverage and treatment outcomes. Making the true extent of the crisis visible is the first step toward demanding accountability and securing the necessary funding.

The medical community must also lead the way by championing the shift from institutional care to community-based models. This involves advocating for the integration of mental health training into all medical and paramedical curricula, especially in primary care. The encouraging data on telehealth adoption and emergency preparedness must also be used to embrace and integrate these technologies into the permanent infrastructure, ensuring that the progress made during a crisis is not lost.

Finally, for citizens and advocates, the report is a powerful tool to demand better mental health care from political representatives. It provides the data necessary to hold governments accountable and to make the case for mental health as a fundamental human right and a national development priority. The crisis is real, but as the Atlas shows, the capacity for transformation is also present. By understanding the numbers and acting on the insights, India can transform its mental health landscape from one of chronic neglect to one of proactive care and genuine human well-being.

Works cited

- Mental Health Atlas 2024 | MHIN, accessed September 14, 2025, https://www.mhinnovation.net/resources/mental-health-atlas-2024

Disclaimer

The content of this blog has been created using a combination of publicly available information, expert references, and AI-assisted tools. While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, the blog should not be considered a substitute for professional advice in fields such as medicine, mental health, or law. The views expressed are for informational and educational purposes only. Readers are encouraged to verify details through official reports, consult qualified professionals where appropriate, and use their own judgment when interpreting the information.