We’ve all been there. Perhaps it’s the colleague who, after watching one YouTube documentary, is suddenly an expert on global supply chain logistics. Or maybe it’s the relative at dinner who explains your own profession to you with the unearned confidence of a seasoned veteran.

In psychology, we call this the Dunning-Kruger Effect. In the real world, we often call it “the loudest person in the room being the least informed.” But while it’s easy to point fingers at others, the most uncomfortable truth about this phenomenon is that it lives in all of us.

The Anatomy of an Illusion: What is Dunning-Kruger?

At its core, the Dunning-Kruger effect is a cognitive bias where people with limited knowledge or competence in a specific domain overestimate their own abilities. Conversely, those with high competence often assume that tasks which are easy for them are also easy for everyone else, leading them to underestimate their relative standing.

The seminal research, titled “Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One’s Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments” (Dunning & Kruger, 1999), established the baseline. They found that students scoring in the bottom quartile on tests of humor, grammar, and logic grossly overestimated their performance. While they scored in the 12th percentile, they estimated they were in the 62nd.

The “Double Burden”

Why does this happen? Dunning and Kruger argued that the unskilled suffer a “double burden.” The same lack of knowledge required to perform a task is the very knowledge required to evaluate that performance. If you don’t know the rules of grammar, you can’t possibly know when you’ve broken them. You are, quite literally, unaware of your own unawareness.

Climbing the Mountain (And Falling Off)

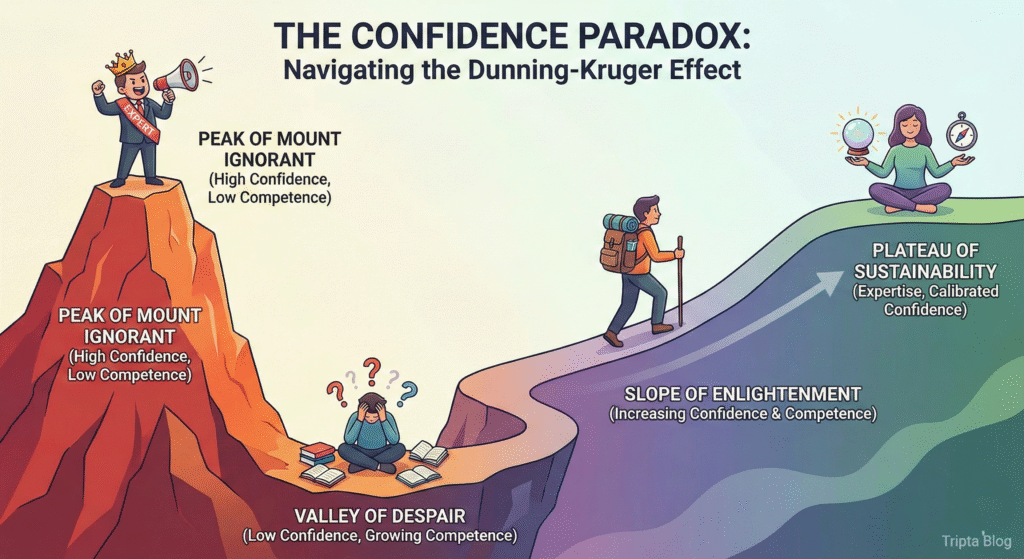

To understand how this plays out in your career or social life, we have to look at the Confidence vs. Competence curve.

Phase 1: The Peak of Mount Ignorant

When you first start learning a subject, your confidence skyrockets. You’ve learned the jargon, you understand the basic “vibe,” and you feel like a genius. This is “Mount Ignorant.” Here, you don’t know enough to realize how complex the field actually is.

Phase 2: The Valley of Despair

As you continue to study, the “unknown unknowns” become “known unknowns.” You realize the field is vast, nuanced, and difficult. Your confidence craters. This is often where people quit, feeling they “don’t have what it takes,” when in reality, this dip is the first sign of actual growth.

Phase 3: The Slope of Enlightenment

This is the slow, steady climb. You are gaining true competence. Your confidence begins to rise again, but it’s a quiet, grounded confidence.

Phase 4: The Plateau of Sustainability

You are now an expert. Interestingly, at this stage, you might experience Imposter Syndrome. Because you find the work manageable, you assume everyone else does too, and you may underestimate your unique value (Kruger & Dunning, 1999).

3. The Professional Pitfall: Dunning-Kruger at Work

In a corporate environment, this effect isn’t just annoying; it’s expensive. It leads to “miscalibrated” leadership, where the most confident—rather than the most competent—are promoted.

The “Confidence Heuristic”

Research suggests that humans have a natural tendency to use confidence as a proxy for competence (Price & Stone, 2004). In meetings, we instinctively trust the person who speaks first and with the most conviction. This is a survival instinct gone wrong in the modern office.

How to handle it in the workplace:

- For Managers: Stop asking “Can you do this?” Overconfident employees will say “Yes” before they even understand the question. Instead, ask for a work breakdown structure. “Walk me through your methodology for the first three steps.” If they can’t explain the how, they don’t have the know.

- The Power of the Pre-Mortem: Invented by psychologist Gary Klein, a pre-mortem involves imagining a project has failed and working backward to determine why. This forces overconfident individuals to acknowledge risks they previously ignored (Klein, 2007).

- Culture of Feedback: High-performing organizations like Netflix or Pixar thrive on “radical candor.” By making objective feedback a daily habit, you lower the social cost of correcting someone’s “Mount Ignorant” moment.

4. Social Circles and the “Know-it-All”

Socially, the Dunning-Kruger effect is the ultimate vibe-killer. It’s the friend who dominates a conversation about climate policy after reading one headline.

Why it’s Hard to Correct

Correcting someone in a social setting is risky because humans are “socially motivated” (Kunda, 1990). We want to be liked and to belong. Telling a friend they don’t know what they’re talking about triggers a “threat response,” making them dig their heels in further.

Strategic Social Maneuvers:

- The Socratic Pivot: Instead of saying “You’re wrong,” ask, “That’s a bold take; how does that factor in [specific nuance]?” This forces them to confront the limits of their knowledge without you having to be the “bad guy.”

- Intellectual Humility as a Trend: Lead by example. Use phrases like, “My current understanding is…” or “I’m still trying to wrap my head around this.” Research shows that people who demonstrate Intellectual Humility are more Liked and perceived as more intelligent (Porter & Schumann, 2018).

- The “Expertise Shift”: If someone is talking nonsense about a topic, steer them toward something they actually know. “That’s an interesting theory on the economy—speaking of which, how is that new project at your firm going? You mentioned you were handling the data side.” You’ve moved them from a Peak of Ignorant to a Peak of Actual Knowledge.

5. The Mirror: Are YOU the Dunning-Kruger Case Study?

Here is the hard truth: You are currently on Mount Ignorant about something.

A 2003 study by Dunning and colleagues found that people generally have a “top-down” view of their abilities. If we think we are “generally smart,” we assume we will be smart at everything we try (Dunning, Meyerowitz, & Holzberg, 1989). This is the Halo Effect working against our self-awareness.

How to Stay Calibrated

- The “Rule of Three”: Before you form a hard opinion, find three credible sources that disagree with you. If you can’t accurately summarize their arguments, you haven’t learned enough yet.

- Check Your Emotional Temperature: If you feel an intense rush of “certainty” or “righteousness” during a debate, that’s your amygdala talking, not your expertise. Experts are rarely 100% certain; they speak in probabilities.

- Seek Out “Red Teams”: In cybersecurity, a Red Team’s job is to find holes in a system. Find a friend or mentor who is a “Red Team” for your ideas. Ask them, “What am I missing here?”

Conclusion: The Goal is Not Perfection, but Calibration

The Dunning-Kruger effect isn’t a “stupidity” problem; it’s a “metacognition” problem (thinking about thinking). The world is increasingly complex, and none of us can be experts in everything.

The most successful people in the workplace and the most pleasant people in social circles are those who have mastered calibration. They know where their circle of competence ends and where the “here be dragons” territory begins.

As Charles Darwin famously wrote in The Descent of Man: “Ignorance more frequently begets confidence than does knowledge.” So, next time you feel like you’ve mastered a new skill in a weekend, take a deep breath, step off the peak, and start the long, rewarding trek through the valley. The view from the Slope of Enlightenment is much better anyway—and the air is a lot less thin.

References & Further Reading

- Dunning, D., & Kruger, J. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

- Price, P. C., & Stone, E. R. (2004). Intuitive confidence profiling: Is overconfidence interpreted as a sign of knowledge? Mind & Society.

- Klein, G. (2007). Performing a Project Premortem. Harvard Business Review.

- Porter, T., & Schumann, K. (2018). Intellectual humility and openness to the opposing view. Self and Identity.

- Dunning, D., Meyerowitz, J. A., & Holzberg, A. D. (1989). Ambiguity and self-evaluation: The role of idiosyncratic trait definitions in self-serving assessments of ability. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.