Science is finally catching up to what many families have instinctively known for generations: trauma and the predisposition for addiction can be passed down. But if history can be written into our biology, it can also be edited.

At Tripta Foundation, we often hear clients describe their struggles with addiction or chronic anxiety as feeling like a “generational curse.” They look at their family trees and see the same patterns repeating—the same struggles with substances, the same inability to handle stress, the same shadowed corners of mental health—echoing from grandparents to parents to themselves.

For decades, society has debated whether this is “nature” (a fixed genetic destiny) or “nurture” (learned behavior from a chaotic environment). Today, groundbreaking science tells us that both answers are incomplete. There is a third, crucial element at play, bridging the gap between our biology and our experiences. It is called Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance.

This concept is revolutionary for the field of addiction and mental health recovery. It provides a biological framework for understanding why certain families are more vulnerable, not because they are “broken,” but because their biological software has been programmed by the experiences of those who came before them.

The Missing Puzzle Piece: What is Epigenetics?

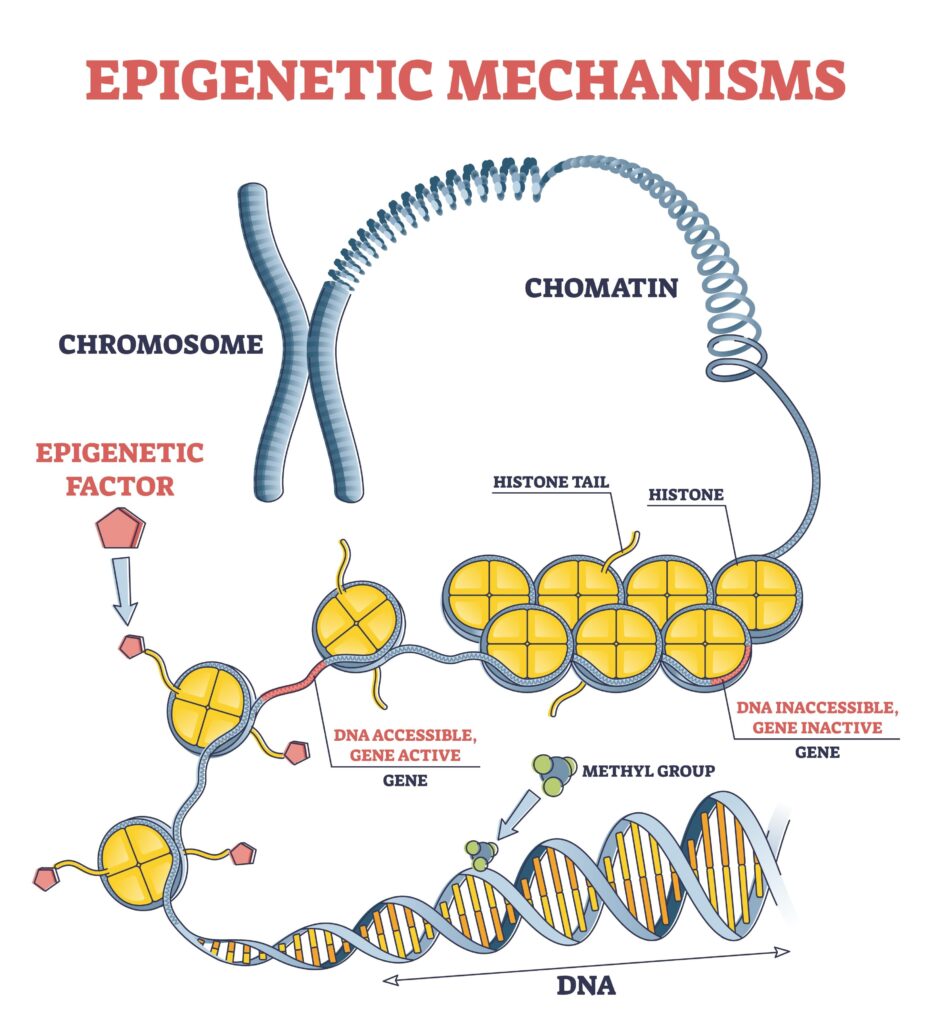

To understand how trauma is inherited, we first need to understand epigenetics. Think of your DNA as an enormous instruction manual—a massive cookbook containing every recipe needed to build a human being. Every cell in your body has the exact same cookbook. But if every cell has the same instructions, why does a heart cell look and act completely distinct from a brain neuron?

The answer is the epigenome. If DNA is the cookbook, the epigenome is a collection of bookmarks, highlights, and paperclips stuck onto the pages. These marks tell the cell: “Cook this recipe right now,” “Ignore that recipe entirely,” or “Cook this one, but only add half the salt.”

Epigenetics (literally meaning “above genetics”) does not change the actual sequence of your DNA. You have the same genes you were born with. Instead, epigenetics controls gene expression—whether a gene is turned “on” or turned “off” (Carey, 2012).

Our bodies use clever biological mechanisms to do this switching. The two most common are:

- DNA Methylation: A tiny chemical “cap” attaches itself to the start of a gene. This cap usually acts like a silencer, turning the gene off.

- Histone Modification: Your DNA is wrapped around protein spools called histones. If the DNA is wrapped too tightly, the gene is hidden and inactive. If it relaxes, the gene becomes accessible.

The “Ghost in Your Genes”

The problem arises when the environment is chronically stressful or toxic. When an individual experiences severe, prolonged trauma, their epigenetic markers shift to help them survive. For a long time, scientists believed that when a new embryo is formed, these marks were wiped clean—a biological “factory reset.”

We now know that some marks are “stubborn.” They escape the erasure process. In her landmark research, Dr. Rachel Yehuda found that Holocaust survivors and their children shared similar epigenetic alterations in the FKBP5 gene, which regulates stress (Yehuda et al., 2016). This means the biological memory of trauma was transmitted from parent to child, even though the children never experienced the Holocaust themselves.

The Biological Chains of Addiction

At Tripta, we see how this plays out in the real lives of those seeking recovery. Research suggests that substance use disorders (SUD) are not just “bad habits” but are fueled by specific epigenetic remodeling in the brain’s reward circuitry.

1. The Muted Pleasure Receptor (Tolerance)

Chronic drug or alcohol use causes the brain to “protect” itself by turning down the volume of pleasure signals. This happens through increased methylation of the OPRM1 gene (the mu-opioid receptor). When this gene is “muted,” the brain produces fewer receptors. This is the biological bedrock of tolerance: the individual becomes biologically “numb” and requires more of the substance just to feel baseline normal (Nielsen et al., 2012).

2. The Switch That Gets Stuck “On” (Craving)

Why are cravings so persistent? Chronic use triggers the accumulation of a protein called (Delta)FosB in the Nucleus Accumbens, the brain’s reward center. Dr. Eric Nestler, a pioneer in this field, describes (Delta)FosB as a “molecular switch” for addiction. Once flipped, it remains stable for weeks or months, driving compulsive cravings and structural brain changes long after the substance has left the system (Nestler, 2013).

3. The Broken Stress Thermostat

Many clients at our rehabilitation centers struggle with a “broken” stress response. Trauma—whether personal or inherited—can leave the body’s central stress system, the HPA axis, in a state of permanent “high alert.” In studies of “The Dutch Hunger Winter,” children born to mothers who survived famine showed decreased methylation of the IGF2 gene, which impacted their metabolism and stress regulation for the rest of their lives (Heijmans et al., 2008).

For a person with this inherited hyper-sensitivity, the world feels naturally unsafe. Substances that offer temporary calm, like alcohol or opioids, become an instinctive form of “survival medicine.”

The Good News: The Power of Reversibility

If the story ended here, it would be a tragedy of biological fate. But the most exciting discovery in modern science is that the epigenome is plastic. Unlike a genetic mutation, epigenetic marks can be reversed.

The same mechanisms that allowed a negative environment to turn a “bad” gene on can be used to turn it back off. This is the scientific foundation of hope. While trauma writes “sticky notes” in our genetic cookbook that say “be anxious,” positive experiences and therapy can act as a biological eraser.

Rewriting the Future

This science validates the holistic approach we champion. We know that talk therapy alone isn’t always enough to reach these deep molecular switches. Recovery requires an environmental shift:

- Mindfulness and Meditation: Regular practice has been shown to down-regulate pro-inflammatory genes and calm the overactive HPA axis (Kaliman et al., 2014).

- Aerobic Exercise: Physical activity increases BDNF (Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor), essentially “Miracle-Gro” for the brain, which helps neurons forge new, healthy pathways (Vaynman et al., 2004).

- Safety and Connection: A supportive community at a wellness home provides the consistent signal of safety that the epigenome needs to begin “reprogramming” itself toward health.

The journey of recovery is difficult because you may be fighting biological currents that have been gaining strength for generations. But knowing why it is hard makes it endurable. Your past may be written into your body, but the pen is now in your hand. Through conscious healing, you have the power to edit the ledger for yourself and for the generations to come.

References

- Carey, N. (2012). The Epigenetics Revolution: How Modern Biology Is Rewriting Our Understanding of Genetics, Disease, and Inheritance. Columbia University Press.

- Heijmans, B. T., Tobi, E. W., Stein, A. D., Putter, H., Blauw, G. J., Susser, E. S., … & Lumey, L. H. (2008). Persistent epigenetic differences associated with prenatal exposure to famine in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(44), 17046-17049.

- Kaliman, P., Lomeña, F., Rossi, R., Casañas, A., Okende, M. N., Soler, J., … & García-Campayo, J. (2014). Rapid changes in histone deacetylases and inflammatory gene expression in expert meditators. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 40, 37-44.

- Nestler, E. J. (2013). Cellular basis of memory for addiction. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 15(4), 431-443.

- Nielsen, D. A., Ji, F., Yuferov, V., Ho, A., He, C., Ott, J., & Kreek, M. J. (2012). Genotype-age interactions in DNA methylation of the OPRM1 promoter in postmortem human brain. Epigenetics, 7(11), 1332-1344.

- Vaynman, S., Ying, Z., & Gomez-Pinilla, F. (2004). Hippocampal BDNF mediates the efficacy of exercise on synaptic plasticity and cognition. European Journal of Neuroscience, 20(10), 2580-2590.

- Yehuda, R., Daskalakis, N. P., Bierer, L. M., Bader, H. N., Klengel, T., Holsboer, F., & Binder, E. B. (2016). Holocaust exposure induced intergenerational effects on FKBP5 methylation. Biological Psychiatry, 80(5), 372-380.