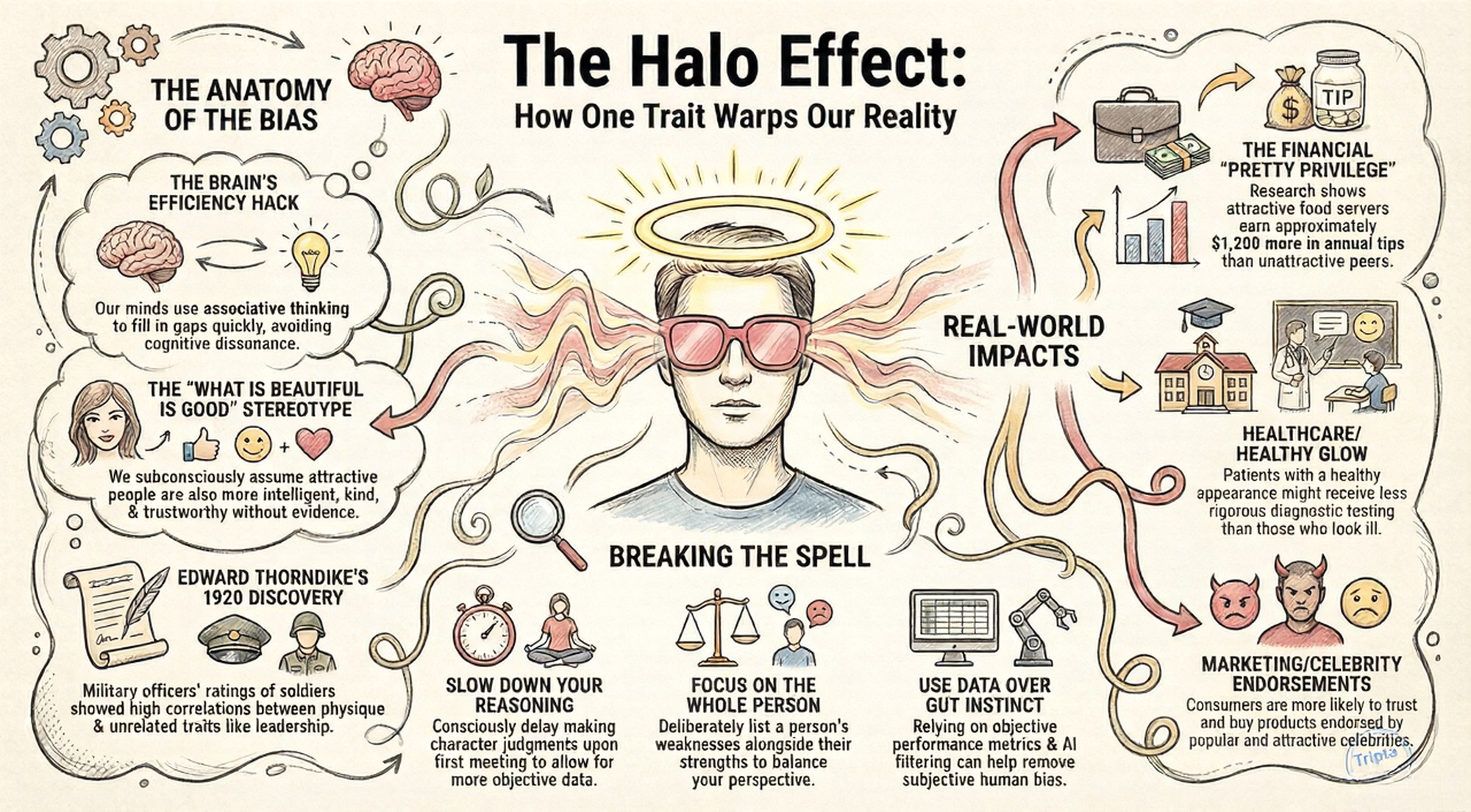

In the intricate theatre of social and professional hierarchies, we often flatter ourselves by believing our judgments are the result of objective, analytical reasoning. However, behavioural science reveals a far more pervasive and elusive reality. We are perpetually guided by the “Halo Effect,” a ubiquitous force that acts as the silent architect of our decision-making. Far from being a mere quirk of personality, the Halo Effect is a fundamental perception error that distorts reality, compelling us to use a single salient trait as a heuristic for a person’s entire character.

For the professional navigating the executive suite or the student entering a new seminar, the “So What?” of this phenomenon is profound. This bias leads to the misattribution of competence, the masking of critical red flags, and the systemic exclusion of talent based on superficial morphological characteristics. To achieve true psychological clarity, we must recognize that this unearned “glow” often blinds us to the objective data required for sound judgment.

Key Concept: The Halo Effect

The Halo Effect is a cognitive bias wherein an observer’s overall impression of a person, brand, or product—often based on a single positive characteristic like physical attractiveness or charm—positively influences their evaluation of that entity’s unrelated traits, such as intelligence, morality, or professional capability.

To master our judgments, we must first look back at how this phenomenon was discovered in the rigorous environment of early 20th-century military psychology.

From the Battlefield to the Boardroom: The History of the Halo

The conceptual roots of the Halo Effect lie in the 1920 research of psychologist Edward Thorndike. In his seminal paper, “A Constant Error in Psychological Ratings,” Thorndike identified a systemic flaw in how commanding officers evaluated their soldiers. He observed that officers were psychologically incapable of treating distinct qualities as independent variables.

Instead, Thorndike identified a “constant error” where an officer’s perception of a soldier’s “Physique”—defined by specific cues like neatness, voice, and energy—created a halo that colored technical assessments of leadership and character. This historical insight demonstrates that the “executive presence” sought in modern boardrooms is often merely the evolved descendant of the military “bearing” Thorndike studied a century ago.

Thorndike’s Military Observations (1920)

| Trait Observed (Cues) | Assumed Correlation | Psychological Impact |

| Physique (Voice, Neatness, Energy) | Intelligence | Higher physical “neatness” led to inflated ratings of mental acuity. |

| Physique (Bearing, Physique) | Leadership | Soldiers with “good bearing” were assumed more capable of command. |

| Physique (Neatness, Presence) | Character | Physical bearing was conflated with loyalty and dependability. |

This bias persists because our brains prioritize efficiency through associative thinking, even when those associations are logically fallacious.

The Digital Upgrade: AI Filters and the “Pretty Privilege” Paradox

In the digital era, the Halo Effect has undergone a significant technological evolution. Recent research by Gulati et al. (2024) utilizes Social Signal Processing to analyze how AI-based beauty filters intensify this bias. Their large-scale study confirmed that individuals with “beautified” images received statistically higher ratings for intelligence and trustworthiness.

Crucially, Gulati identified a saturation effect—a threshold where extreme filters or professional makeup may actually mitigate the bias. This finding is vital as it “resolves conflicting findings” in existing literature; while moderate beautification amplifies the halo, extreme digital alteration can cause the illusion to break, potentially weakening the perceived credibility of the subject.

Three Ethical Concerns of Digital Halos

• Artificial Credibility: AI filters can manipulate consumer trust, leading audiences to ascribe unearned expertise to influencers based on filtered morphological traits.

• The Humanness Gap: Research (Alaei et al., 2022) suggests a disturbing trend where less attractive individuals are judged as “less human,” a cognitive dissonance that leads to profound systemic exclusion in digital spaces.

• Distorted Meritocracy: The digital halo reinforces the “what is beautiful is good” stereotype, making it increasingly difficult to evaluate content or talent on its intrinsic merit.

The Economics of Appearance: Impact on Career and Income

The Halo Effect is not merely a psychological curiosity; it functions as a form of “Pretty Privilege” that translates directly into financial currency. This is most visibly demonstrated in the service industry. Parrett (2015) identified a stark $1,200 annual tip gap for food servers, where attractive staff out-earn their colleagues for the same level of service. This highlights the irrationality of the bias: the financial reward is decoupled from the actual performance.

In the corporate sector, managers frequently fall victim to the “Success equals Capability” fallacy. A single positive trait—such as professional dress or “enthusiasm”—can lead to an inflated performance appraisal, where a high-performing salesperson is assumed to be an inherently gifted manager despite having no demonstrated leadership skills.

Workplace Bias Checklist for Managers

• The Enthusiasm Mask: Is a subordinate’s positive attitude overshadowing a measurable lack of technical skill? (Source: Verywell Mind)

• The Contrast Error: Am I comparing this employee’s performance to an idealized “schema” or prototype rather than objective data?

• The Single-Trait Trap: Am I generalizing an employee’s excellence in one specific task to mean they are qualified for an unrelated promotion?

• Morphological Bias: Is this person’s “professional look” or physical presence influencing my rating of their intelligence?

The Classroom Filter: Grading, Expectations, and the Student Experience

The “halo” begins to warp reality long before the first job interview. In educational settings, the Halo Effect influences the trajectory of a student’s life through teacher expectations. Hernandez-Julian & Peters (2017) provided a compelling “So What?” by contrasting traditional classrooms with online environments. They found that students rated as “above-average” in attractiveness earned significantly lower grades in online courses, where the absence of a physical “halo” forced instructors to grade solely on performance.

Furthermore, the bias extends even to name recognition, where the “halo” is triggered by text rather than image.

“Teachers’ evaluations of children’s performance were associated with stereotyped perceptions of the students’ first names… even experienced teachers fell for the trap, as short essays with names associated with positive stereotypes [attractive/popular names] received significantly higher grades.” — Harari & McDavid (1973)

Love Through Rose-Colored Glasses: The Halo in Relationships

In romance, the Halo Effect is the engine behind the “rose-colored glasses” phenomenon. We frequently identify a single charming trait—such as humor or professional success—and use it to mask shortcomings. This leads to the minimization of one’s own needs, as we assume a partner’s “generosity” will eventually compensate for serious emotional incompatibilities.

Red Flag vs. Halo: A Comparison Chart

| The Halo (Bias-Driven Idealization) | The Red Flag (Genuine Compatibility Issue) |

| “They are so successful; they must be a reliable partner.” | They consistently fail to show up for emotional commitments. |

| “They have a great sense of humour; they didn’t mean to be mean.” | Their “jokes” are often at your expense or dismissive of your feelings. |

| “They are so attractive; I’m sure we’ll work out the details.” | You have fundamental differences in life values and goals. |

The Dark Mirror: Understanding the “Horn Effect”

The inverse of the halo is the Horn Effect, or the “Reverse Halo.” This occurs when a single negative trait creates a pervasive negative evaluation. In the landmark Nisbett & Wilson (1977) study, students watched a “Cold Professor” interact. Because the professor acted distant (the single negative trait), students rated his accent and mannerisms—which were objectively neutral—as “irritating.”

The 3 Primary Triggers of the Horn Effect

1. The “Cold” Heuristic: A single distant interaction can color all other attributes, making expertise seem like arrogance.

2. Unattractive Bias: The assumption that someone who does not meet conventional beauty standards is also less intelligent or unkind.

3. The Mannerism Generalization: Allowing a neutral trait (like an accent or a specific gesture) to trigger a dismissal of the person’s entire character or competence.

The Nuance of Reality: When the Halo Fades

While powerful, the Halo Effect is more limited than previously thought. Sophisticated analysis by Lucker et al. (1981) argues that the halo does not apply to all personality traits; rather, it narrows specifically to evolutionary and social categories like “Sexiness, femininity/masculinity, and liking.”

Furthermore, recent research (Fultz et al., 2023) suggests that the halo’s power is finite. As we move from “zero-acquaintance” to established relationships, other behavioural cues override physical bias.

Myth vs. Reality: The Truth About the Halo

• Myth: Physical attractiveness is the permanent, sole determinant of whether someone is liked.

• Reality: Nonverbal expressivity (facial movement and gesturing) and agreeableness are independent predictors of liking. By nine weeks of acquaintance, these behavioural qualities override initial physical bias.

• Myth: The Halo Effect is an all-powerful, unshakeable force.

• Reality: The halo is “more limited than previously implied.” While it impacts first impressions, actual behaviour becomes a far stronger predictor of long-term social value.

Conclusion: Breaking the Spell and Masterful Decision-Making

To achieve “Wellness through Awareness,” the modern professional and student must engage in Cognitive Debiasing. By understanding the heuristics that lead to these perception errors, we can slow down our reasoning process and look beyond the superficial. This is not merely a psychological exercise; it is an essential skill for achieving equity and accuracy in a world increasingly dominated by digital and physical “halos.”

How to Avoid the Trap

• Practice Deliberate Reasoning: Consciously discourage character judgments during a first meeting to prevent “associative thinking” from filling in the gaps.

• Seek Outside Perspectives: Utilize objective data or the opinions of those not currently “under the spell” of a person’s initial charm.

• Focus on the Whole Person: Actively seek information that contradicts your initial impression to prevent confirmation bias from locking the halo in place.

Final Takeaway

At the heart of the Tripta Foundation’s mission is the empowerment of individuals through psychological clarity. By stripping away the “invisible lens” of the Halo Effect, we can move toward a more authentic, evidence-based understanding of ourselves and those around us.

——————————————————————————————————————

This report aims to foster deeper awareness of the cognitive biases that shape our daily lives. For more insights into behavioural science and decision-making, stay connected with our ongoing research updates.